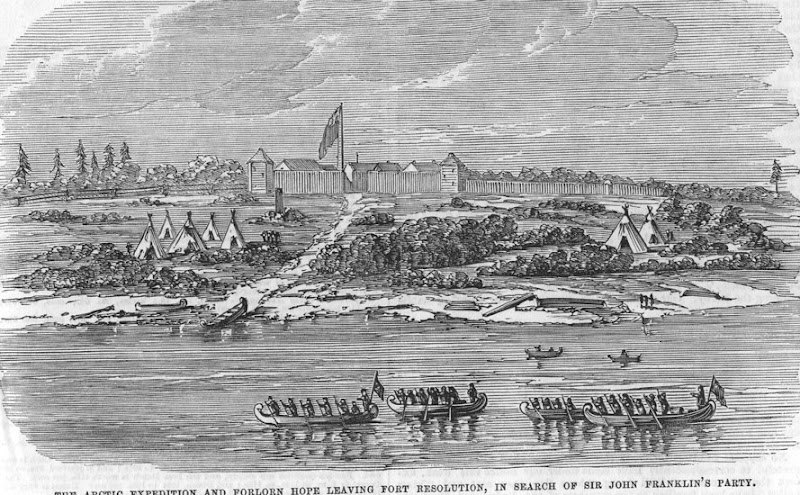

Engraving from an 1850's U.S. newspaper describing another failed search-and-rescue attempt.

Franklin's lost expedition was a doomed Arctic exploration led by Sir John Franklin in the 19th century. The 134 strong expedition (24 officers and 110 men) died one by one from disease, inexplicable violence, creeping madness or from the terrible arctic cold. They each died in a strange part of the ceiling of the world were temperatures regularly reach -40°F or -23°C degrees below zero.

The expedition's goal was to find the fabled Northwest Passage. This was no small task. Most of the year, a series of frozen peninsulas and straits that make up the Canadian Arctic are covered with rough, heavy ice. The impasse separated the Atlantic and the Arctic Ocean near Alaska.

This situation forced hundreds of years of maritime traffic around Africa and South America before the Panama Canal was built in 1914.

Finding the Northwest Passage in 1845 was every bit a lucrative prospect to the English empire. They had intended to send their best men and equipment north to reach this goal.

Two modern marvels, steamships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, helmed by experienced captains James Fitzjames and Francis Crozier respectively, were selected for the doomed expedition. These ships were at the height of modern technology in their day. They were equipped with conventional sails plus steam engines. They were sturdy at 360+ tons apiece with iron rudders and propellers and had on-board heat that was well suited for arctic exploration.

The ships sailed north from Greenhithe just outside of London, England in May of 1845. The expedition meant to sail through the Northwest Passage across the far northern coastal region of Canada was fully underway.

A Royal Navy officer and experienced explorer, Sir John Franklin led this expedition. Franklin had served on three previous Arctic missions, the latter two as commanding officer. His fourth and last, undertaken when he was 59, was meant to traverse the Northwest Passage.

A Royal Navy officer and experienced explorer, Sir John Franklin led this expedition. Franklin had served on three previous Arctic missions, the latter two as commanding officer. His fourth and last, undertaken when he was 59, was meant to traverse the Northwest Passage. If anyone could breach the passage it was thought that Franklin could. He had braved several calamitous adventures in Canada's Northwest Territories as a young man. Between 1819 and 1822, Franklin lost 11 of his 20 man expedition to the Coppermine River. He nearly died himself when he fell through a patch of ice. Many men died of starvation. The survivors were forced to eat lichen.

Franklin ventured back to the Northwest Territories in 1825. There he became the first Englishman, and only the second European, to explore the entirety of the longest river in Canada, the Mackenzie. Fort Franklin stands there today in the spot where he spent the winter. It was there he discovered the ocean remained frozen even in summer.

But Franklin still managed to return to England in September 1827. There he was knighted and began an unfulfilling career as a lieutenant governor of Tasmania near Australia. He must have welcomed the chance to get back to the Northwest territories. In 1845, he had his chance.

As the ships sailed north, through the ice-choked waterways, the expedition began enduring fatalities. Franklin had lost men before to the cold and must have rallied his men onward.

Then Franklin's ships, the Erebus and Terror, both became hopelessly icebound. The boats were theorized to have found themselves frozen in the thick ice banks of the Victoria Strait near the north side of King William Island deep in the Canadian Arctic.

After many failed attempts to free the vessels the entire expedition complement, including Franklin and his remaining men, began to suspect that they would be lost in the ice and snow 4,000 miles from anything resembling home.

A few skeletons of Franklin's doomed expedition are found on King William's Island in the 19th century.

When Franklin's expedition failed to report for three years, in 1848, the British Admiralty began to send out rescue parties. In 1850, England offered a £20,000 reward "to any Party or Parties, of any country, who shall render assistance" to Franklin and his men.

That's £1,752,100 or over $2.8 million USD as of 2014. That generated some interest.

In 1854, adventurer John Rae, while surveying the Boothia Peninsula for the Hudson's Bay Company, discovered disturbing evidence of the lost men's fate. Rae met an Inuit native near Pelly Bay (now Kugaaruk, Nunavut) in April of 1854, who described a group of 35 to 40 white men who had died of starvation near the mouth of the Back River.

Other Inuit Rae encountered also confirmed this story, which included reports of cannibalism among the dying sailors. These Inuit showed Rae many objects that were identified as having belonged to Franklin and his men - including engraved silverware from Erebus Captain James Fitzjames.

In 1857, nearly 12 years after Franklin sailed from England, an expedition led by Sir Francis McClintock, discovered a number of written messages indicating that the Erebus and Terror had become stuck in the ice in September 1846. According to the sailor's own accounts, during the next year and a half nine officers, including Sir John Franklin (June 1847), and fifteen sailors died.

The notes record that in April of 1848, the surviving members of the expedition (of up to 105 sailors) decided to abandon the ships and walk across the ice. Their goal was to make it 120 miles south to a river where they could row further south to a trading post.

Further English and American expeditions sent to recover Franklin and his men discovered only empty frozen wasteland and desperate messages - not crewmen.

It was beginning to look like that no one had survived. As more abandoned equipment and messages were found it became easy to see why the survivors didn't make it back to civilization: the men used extremely poor judgment. Not only had they tried to drag a 1,200-pound lifeboat across the ice, they had selected an assortment of strange items to fill the boat: silk handkerchiefs, perfumed soap, six books, tea, silverware and chocolate. They carried these items to possibly to trade with but this made it impossible for a 100+ man column to survive the 120 mile journey w/out food, extra clothing, tents or blankets.

The fact remains that they did not survive. The bitter cold trek across the ice barrens claimed every man before they could trade these trinkets and baubles with anyone.

In 1859, another international search-and-rescue effort discovered a typed note written in 6 languages (English, French, Spanish, Finnish, German and Dutch). This note had several dates and signatures scrawled on it. "May 1847" was scrawled in the lower right corner along with the Erebus's Captain Fitzjames' signature. This message, giving the latitude and longitude of the ice-bound ships was found on King William Island.

This note was completely without any details about the expedition's true fate. More searches continued throughout much of the 19th century. None of them turned up survivors.

In 1981, Owen Beverly Beattie and a modern group of explorers, also armed with the latest technology and gadgetry of the age, set out to find the remains of the lost men of Franklin's doomed voyage. This expedition searched the islands surround Victoria Strait. Soon a handful of the doomed crew of the Erebus and Terror, lost for nearly 150 years in the icy tundra began to be recovered at improvised island grave sites.

Due to global warming uncovering vast amounts of permafrost in the Arctic, Beattie's team had a better time of it than Sir McClintock - to be sure. And what Beattie's team found found for lack of a better word were ice mummies. These men's bodies were well-preserved, undisturbed for many long decades. In fact, their faces still betrayed the cruel, icy manner of their deaths - forever frozen in time.

Petty Officer John Torrington at his final resting place where he died sometime between 1846-1850.

In 1984 and 1986, Beattie found and exhumed the frozen bodies of Petty Officer John Torrington, Able-bodied Seaman John Hartnell and Royal Marine William Braine, on Beechy Island. Beattie noticed highly elevated levels of lead in the sailor's tissues. He was able to trace the source to the expedition's food supply.

Weeks before Franklin set sail, a contractor named Stephen Goldner worked frantically on the large and hasty order of 8,000 tins ordered by the voyage. The tins were quickly manufactured. They were found to have lead soldering sealing them. Beattie found that the tins were coated inside and out with toxic lead. In his words the lead was "thick and sloppily done, and dripped like melted candle wax down the inside surface".

Lead poisoning is known to cause insanity. It causes delirium, cognitive deficits, tremors, hallucinations, and convulsions.

Coupled with the brutal cold and the extreme isolation of being trapped at sea with no hope of rescue: it is highly probably that many of these men went mad. Evidence of cannibalism exists in the form of gnaws and cut marks found on human bones discovered on the surrounding islands in Victoria Strait.

Both ships would remain lost and entombed somewhere in the thick Canadian Arctic ice until October of 2014. A federally funded Parks Canada expedition led by underwater archeologist Ryan Harris found HMS Erebus. Using sonar, drones and several dives into the icy arctic water, Harris discovered that the ice around Erebus had thawed and the ship had sunk the to the bottom of the Strait near the remote inlet of Banks Island.

Ryan Harris discovers the final resting place of the HMS Erebus in October of 2014.

Harris, in an interview with CBC, said that during a dive he and his colleague Jonathan Moore were able to drop down between the exposed beams of the Erebus and "peer around" the interior, including the crew's mess. The pair could see below decks through old skylights and other openings but did not enter the interior of the ship.

This discovery did not go unnoticed. Prime Minister of Canada, Stephen Harper, congratulated Harris and his team in a nationally televised award presentation.

As of today the HMS Terror still remains lost.

It took 168 years and generations of dedicated explorers to only partially discover the fate of the the lost expedition. These bold men, who were trapped and set upon by unending ice and blinding snow, were slowly driven to utter madness at the edge of the known world.

God rest their souls.

References:

Wikipedia, King William's Island

Wikipedia, The Note

Archeology Institute Of America (AIA), Northwest Passage Saga

Amazon, The Terror by Dan Simmons New York : Little, Brown and Co., 2007.

Amazon, Frozen in time: The fate of the Franklin Expedition by Owen Beattie & John Geiger, Vancouver : Greystone Books, c1998.

YouTube, Ice Mummies

World News, Franklin Expedition

No comments:

Post a Comment